Urmia – UNVEILED IN KHOZRAWA

nala4u.com / shlama.be

The region of Lake Urmia in the northwest of Iran borders on Turkey. Since ancient times that area is the homeland of Assyrian Christians, who are nowadays a small minority in the Urmia region. It is a remote place, seldom explored by western visitors. This is the story of a voyage to the village of Khozrawa, still haunted by the memory of the murder in 1918 on the Assyrian Patriarch Mar Shimun. August Thiry

Mona

Mona in Urmia

Mona drives the old land rover through the centre of Teheran. A fast moving fortress, its mighty bumpers and steel frame in front force much smaller Iranian Peykan cars out of the way. We pass a pickup truck with a bunch of bearded macho-types standing upright in the back part. They make repelling gestures and yell. What is the matter with them? ‘Never mind,’ says Mona. ‘Just male talk, I am used to it.’ She is wearing the chador-like black upper dress for Iranian women, but her veil is just a thin red scarf on the back of her head. Uncovered blond hair, red lips, a Kent cigarette between two fingers – Mona is by no means the type of Muslim woman that fits into the general pattern of today’s Iran.

Mona is 30 years old, not married and Christian, which is an almost unbelievable combination in this country, strictly dominated by the successors of ayatollah Khomeini. She is the daughter of Violet Sargizi, a singer of religious hymns and popular folk songs, who regularly gives performances for the Kurdish community in Western Europe. She is not Kurdish however. The Sargizi family are Assyrian Christians from the region of Lake Urmia in so-called Persian Azerbaijan, the remote northwest province of Iran

Teheran is a gigantic pandemonium under a veiled summer sky. Extremely hot and dusty, wrapped in polluted air and traffic noise. I have not even visited the Holy Shrine for the Great Ayatollah to the south of the capital. Nor the blood fountain on the military cemetery behind that mausoleum. During the war against Saddam’s Iraq in the eighties of the last century this famous fountain sprayed dark red water to honour the young Shiite-martyrs who gave their blood and their life for the sake of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Mona tips the ash from her Kent cigarette and starts telling about Khomeini’s funeral. Immense crowds were pushing towards the open coffin with the corpse of the ayatollah. Official reporting stated that all these thousands of people wanted to get a small piece of the holy shroud, because they loved their great leader that much. Mona still seems to be impressed by that outburst of mass hysteria. But she never shared the intense feelings of the Iranian Shiites. It makes sense: Assyrian Christians apparently had a better and easier life under the secular and western-oriented regime of the last Shah

Professor Pira

We are on our way to Samuel Pira, an Assyrian writer and historian who knows everything about the culture of his people. His house in a quiet sidestreet in the chaotic and overpopulated area of Teheran South is a kind of private museum. It takes a while before the metal gate is turned open in the outside wall that hides the courtyard. Pira is a hook-nosed old man wearing dark glasses. ‘So sorry,’ he mumbles,‘I was absorbed in my own world

Samuel Pira guides us through his house. It is indeed like a museum, with old maps, clay tablets with Assyrian cuneiform script, an old Aramaic Bible, dusty manuscripts, all kinds of objects from long gone traditional village life in the region of Lake Urmia. Professor Pira embraces the whole collection with a broad gesture of his open arms. ‘The best of our homeland is preserved here. We are the last descendants of the old, Assyrians and the first Christians as well

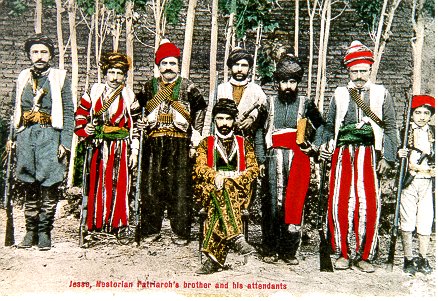

Urmia district – Assyrian guard – Period World War I

Nineveh, close to the city of Mosul in today’s northern Iraq, was the capital of the ancient Assyrian empire. That empire came to an end when Nineveh was destroyed in 612 BC by Babylonians and Medes, the latter being the ancestors of the Kurds. When early Christianity expanded in the Middle East, the Nineveh area became an important centre of the Assyrian-Nestorian Church of the East under Persian rule in Baghdad. At the rise of Islam the Assyrian Christians managed to hold their positions at first, but in the Middle Ages, notably after the Mongolian invasion of the merciless and fanatic Muslim ruler Tamerlane or Timur the Lame from Central Asia, they fled in great numbers to the mountains of Kurdistan in present Turkey. Or they tried to survive in the region of Persian Lake Urmia, close to these mountains

Their religious leader was known by the name Mar Shimun, the hereditary title of that patriarch. During the First World War Mar Shimun Benjamin sided with the British and the Russian forces against Turkey. Together with his people he was driven out of Turkey and they found refuge in the Urmia region. It didn’t last long. In 1918 Mar Shimun was trapped to the north of Urmia and murdered by the Kurdish chieftain Simko. The Assyrian-Christian population then fled in a massive exodus from the Urmia area and later on they got lost in their worldwide diaspora. Nowadays only a few of them are left in their original homeland. Assyrian Christians like the Sargizi family. Or stubborn individuals like Samuel Pira, who has spun himself firmly into the web of his museum

Mona moves her forefinger over the glass plate of a cabinet that contains crumbling prayer books in Neo-Aramaic Sureth, the local language of the Assyrian Christians. Dirt and dust, everywhere. ‘No woman can live here longer than a single day,’ she whispers with a grin on her face. Yet even in the Islamic Republic of Iran professor Pira gained some respect. He shows us an official document: in the late nineties of the last century the University of Teheran nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize. He also calls himself the author of an incredible number of 525 books. But he never got that Nobel Peace Prize and I have seen his books: they are mainly handwritten manuscripts, pinned to the walls of his museum. A peculiar Assyrian – that is the least one can say about Samuel Pira, the lonely custodian who carries the full weight of the Assyrian past

Salomon’s Throne

Before the First World War an important part of the population of the city of Urmia (Orumiye) on the lake with the same name was Christian. Today there are at the most five thousand Assyrians and some thousand Armenians left in and around the town. The Urmia region is also connected with the much older cult of the fire worshippers, followers of the prophet Zoroaster or Zarathustra. According to one tradition he was born in this area in the sixth century BC. The sacred place Takht-é Suleiman, Salomon’s Throne, is situated to the southeast of Lake Urmia. I want to see it. It is a two days’ journey through barren and sweltering countryside, with Mona driving the land rover

Takht-e Suleiman

The ancient site covers the high platform of a rocky hill, surrounded by the soft green and the reddish brown of mountainous Kurdistan. The majority of the ruined structures here were built in the first centuries AD, when Zoroastrian priests, the magi, were predominant under the reign of the Persian Sassanid dynasty

The day is still young. A cold morning breeze ripples the dark blue surface of the large oval pond in the centre of the site. Two Kurdish workers, apparently engaged by the archaeological team of the site, are squatting down on the waterside. I get a warm welcome. Salaam aleikum. Aleikum salaam. We share the breakfast they have brought with them: hot tea with lumps of sugar, flat slices of wheat bread and some goat cheese. Mona is waiting a bit separately. Not hungry, she has made herself clear. The two men chew their bread and from time to time they gaze suspiciously at her. Bad woman: bold eyes, red scarf, no veil

The Zoroastrian temple at the far end of the site is a labyrinth with narrow passages between solid brick walls. The sanctuary, where the holy fire was burning in ancient times, is now an empty hole. Its stone bottom gathers the dust of ages. I take a rest next to Mona on a rock above the fire temple. A splendid view in front of us. We look out over majestically undulating landscape that fades away towards the horizon in greyish blue

Mona looks tired, she had a bad night. We stayed at Takab, a real dump of a town, but the only place close enough for an excursion to the Zoroastrian site. There was one hotel in Takab and we took two single rooms. I was left in peace. She was bothered the greater part of the night by a sneaky receptionist who kept knocking on her door. Horny freaks, all of them,’ says Mona. ‘Women on their own in this country are hunted like stray cats

Towers of Silence

We are riding to the north, following the left bank of Lake Urmia. Its water surface is a silvery mirror glittering in the strong sunlight. The lake is a dead sea, with an extremely high salt content. ‘You can keep floating on your back for hours,’ says Mona, ‘and when you get out of the water, you look from head to foot like a white zombie.’ From head to foot? Mona refuses to go for a swim while wearing those black clothes like all devote Iranian Muslim women do. ‘We try to find some remote and deserted beach,’ she explains, ‘and we look out for Komité-men.’ It is the popular name in Iran for members of the so-called religious police. They see to it that especially young Iranians – more than half of the population – stick to the strict rules of decent Islamic behaviour

Mona wants me to repeat the story I told her on the ancient site of Takht-é Suleiman. It is about the Towers of Silence. The followers of Zoroaster didn’t bury or burn their dead, since according to their religious conviction such an act would pollute the sacred elements of earth and air. Instead of this they put the corpses on solid rock inside the walls of high towers. Then the vultures in the sky above came down and picked the flesh from the bones of the naked corpses. So, the towers got filled up with white skeletons

‘Sweet Lord, what a way to go,’says Mona. She finds it all most gruesome, that Zoroastrian thing, as she calls it, centuries before her own Sweet lord, Jesus Christ

Shlama at Khozrawa

The Muslim town of Salmas lies at the northern end of Lake Urmia. There we take a side road to Khozrawa, one of the last villages in Persian Azerbaijan that Assyrian Christians can call their own. Terrible things happened in this area during the First World War. In January 1915, Turkish soldiers and Kurdish tribal warriors invaded the place, which in those days counted about seven thousand Christians. The Turkish military staff occupied the building of the French Lazarists, who had a mission in Khozrawa. Kurdish horsemen rushed through the neighbourhood and ransacked the churches. The Christians of Khozrawa who hadn’t fled were rounded up, driven away and finally executed. Their dead bodies were thrown in holes and left to be torn to pieces by birds of prey. Not an ancient Zoroastrian thing it was, but one of the many gruesome details marking the start of twentieth century history

Violet Sargizi

Present Khozrawa is a peaceful place. I get a warm welcome in the large cottage of Mona’s mother. Violet Sargizi is a middle-aged woman. Still slim and firm, with curled black hair, a sharp ironic look in her eyes and a kind of pale glow all over her face. As a singer she is famous among the Assyrian Christians in Iran and abroad

We take a walk through the village. A few elderly men are sitting on a stone bench in the greenish shade of eucalyptus trees. Shlama, they greet, slowly nodding. They are wearing wide baggy trousers and waistcoats decorated with embroidery. Shlama, peace with you. The last Assyrians of Khozrawa, two hundred at the most, make a living by growing fruit. Urmia-grapes without seeds, big dark red cherries, apples and pears… The place is surrounded by orchards and right in the middle of the village they have constructed a cooling house where the fruit is stocked for wholesalers who come from all over Iran to buy Khorzawa fruit

The garden of Violet’s cottage borders the former residence of the Lazarist missionaries, who founded a school for the local children in the late 19th century. In Khozrawa this place is still called the French University. Nowadays it is completely in ruins and even the remnants of the Mar Gewargis or Saint George church on this waste land are invaded by the memorahs of high growing thistles and by other weeds

A bit further on we come across the village cemetery. It is a neglected graveyard, surrounded by a low stone wall; there are massive rectangular graves with Aramaic and Armenian inscriptions on the side. The year of the massacre – 1915 – is often mentioned, it has swallowed many living souls in Khozrawa. A few tombstones are pushed aside and deep holes are dug nearby. It is recent work, done by treasure hunters from elsewhere. ‘Muslims still believe that all Christians here are rich and get buried with their gold,’ says Violet. ‘So you can see, even our dead are not left in peace.’ Her face is glowing in the evening sun. On the way back I want to make a picture of the old Assyrian men in their traditional costumes. Too late, the dark shadow under the eucalyptus trees is empty

Mar Shimun

I came to this place to visit another grave: the grave of the Assyrian patriarch Mar Shimun Benjamin. He was murdered in March 1918 by Kurds and buried in Khozrawa, in former times a place of residence for the Assyrian patriarchs, before they moved their seat to the mountain village of Qodshanes in Hakkari, Turkish Kurdistan

Mar Shimun Benjamin (1887-1918)

Unfortunately, there is no such grave in Khozrawa. Old village people only recall that Mar Shimun’s elder sister had his mortal remains exhumed after the final exodus of the Assyrian population from Urmia in the summer of 1918, the refugees heading for the British in Baghdad. Lady Surma, the patriarch’s sister, also went to London in 1920 to make a plea for the Assyrian cause. Her efforts were in vain. The Assyrian people, the smallest ally of the allied nations in the war against Turkey, was completely neglected at the Paris Peace Conference and scarcely mentioned in the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923. Especially the British chose to forget their vague promises of a kind of homeland for the Assyrians

Mar Shimun’s grave is gone, but I can visit the exact place where he was murdered. It is not far from Khozrawa. Mona’s land rover takes a small gravel road to the place Kohna Shahr, which means Old Town in Persian. It was once the main town of the area and a flourishing commercial centre. In 1918 the Kurdish chieftain Simko had selected the place for a meeting with Mar Shimun, pretending he wanted to enter into an alliance with the Assyrian leader and combine their forces against the Turks. In fact it was a trap: Simko was bribed by the Persian governor at Tabriz, the capital of the whole province. Mar Shimun appeared at the meeting place with his mounted guard. The negotiations at Simko’s place came to nothing. In the meantime armed Kurds had climbed the roofs and surrounded the place. When Mar Shimun was about to leave, Simko gave a sign and the Kurds opened fire on the ambushed Assyrians. Most of them were killed on the spot and among them was patriarch Mar Shimun

Till today Simko’s treacherous act, the fact that he betrayed such an important guest whom he had invited to his own place, is in Assyrian eyes the ultimate proof of Kurdish barbarism. Mar Shimun Benjamin died young. The punishment of the crime came later. In 1930 the Persian authorities at Tabriz deceived Simko with false promises similar to those he had used against Mar Shimun. He was ambushed and killed on the spot

Khozrawa graves

‘You know more about that old stuff than we do,’ says Mona. We are standing under some poplar tress at the edge of a large field covered with boulders and smaller rocks. Erosion has cut out deep tracks everywhere and even the high weeds are scorched in the blistering heat. What was left of the houses of Kohna Shahr is now reduced to heaps of rubble. And then this: out of the blue a Kurdish peasant who crosses the deserted site on his rusty bike; dark eyes glancing under his black and white kefiye headscarf. He nods indifferently at the two strangers while he slowly passes us

There is nothing left of Kohna Shahr but old memories, worn out scars in a bleak landscape. Mona points to a high spot farther away. On the summit of a barren hill I see some kind of stone building, the cube-shaped structure of a small church with the cross on top. Mar Yohannon, explains Mona. On the lower slopes of the hill Assyrian and Armenian Christians are buried. I can hardly distinguish the graves. At least what is left of them. These graves too have according to Mona been opened and robbed. ‘Kurds?’ I ask. ‘Muslims for sure,’ she shrugs

Botticelli Blues

My last evening in Khozrawa. The barbecue in the courtyard of Violet’s cottage is a big feast. The whole village has shown up. Violet sings Assyrian songs. The men dance in a long row, they stamp their feet and move their shoulders. One of Mona’s uncles takes me to a cellar behind the cottage, where homemade wine is stocked in enormous jars. Just look at that’, says the uncle, ‘a smell of honey, the taste of Assyria, ointment for the soul.’ That I remember and also that my glass was refilled again and again later on and that I must have performed Flemish popular folk songs in front of a wavering audience

The next morning I am blinded by the bright sunlight on the blood-red cherries behind the open window of my bedroom, and I have to cope with the glow of Zoroastrian fire burning in my poor head. I got up too late; too late for the excursion we had planned to one of those deserted beaches of Lake Urmia. And then Mona, who would come out of the salty water, completely unveiled, just covered in Botticelli-white. It will never come true. But till today I clearly remember her red scarf, the one that guided me through the Assyrian interior in the northwest of the Islamic Republic of Iran